There are many different ways to make decisions as a community. It’s up to you to find and use methods that work best for your community. Make sure your governance framework aligns with your community’s values in both an aspirational way and in a practical way. Observe how your members act and interact, and use your observations to begin building the initial governance foundation and structure. Your structure can be updated and adapted on an ongoing basis or at a later time.

It is tempting to try and find the “perfect” governance structure and principles right away. To create an effective framework, take time to get to know your members and create a space where their relationships with one another can develop. Provide your members with common ground while the community is still in its early stages by creating basic guiding and decision-making principles.

No matter what type of virtual community you have, some decisions must be made regularly. Use these three common strategies to help guide common decisions more easily and more quickly.

- Get to know your community

Virtual communities require decision-making power to be distributed amongst the members. Learning about your community members and understanding their goals and needs will help you learn how to make decisions as a group. To better understand your members, you can:

- Learn from the interactions and small decisions that are being made within the community.

- Engage in a dialogue with the community to determine a common understanding of what the community is and what areas, topics, or processes will require a decision-making process.

- Observe members and pay attention to how they approach decision-making points.

Next, take what you have observed and use it to create a formal decision-making process.

- Minimal Viable Structure (MVS)

At every stage in your community’s development try to design decision-making mechanisms and processes that are as simplified as possible. This is simplification is called minimal viable structure (MVS). MVS helps to maintain the vitality and creativity of the group over time. For example, if your community is not yet doing commercial activities, it does not need principles and rules for this activity at this time.

During your community’s early stages, it is important to create basic, key decision-making mechanisms and processes that allow your virtual community to properly function by enabling it to make decisions now. These can be edited and updated over time. Be aware of who is involved in developing new decision-making mechanisms and outline a draft process to serve as a starting point.

- Common Agreements

How do virtual communities begin making decisions? For many communities, it begins by linking decision-making structures to their core values and vision. These two elements are the starting point and foundation for common agreements. Common agreements are a simple summary document that details clear and complete information about how the group will operate and why. It is important to reference your MVS when creating common agreements.

In-person meetings are the ideal time to discuss decision-making mechanisms and processes. If possible, collect and document information about domains that require decision-making processes and present them to the group during an in-person meeting. Share your documentation with your group before the meeting and set time on the agenda to discuss decision-making.

It is important to remember that conversations about decision-making structures can create tension, debate, and even conflict among members. This is a normal part of the process. Having a trusted facilitator available to guide the discussion will ease the process and prevent or resolve tension. As common agreements evolve over time, they become more stable. Be cautious about continuously changing community ground rules or decision-making processes. This can create confusion and frustration. Conversely, it is important to remain open and to adjust processes when necessary.

Decisions can be made autocratically: a small group or an individual makes all of the decisions with little or no consultation with others. They can also be made democratically:all members deciding on everything.

While autocracy is counter-community, highly democratic decision-making can be a barrier to involvement for some members. Decisions that are made using a democratic process can get delayed by time-consuming consultation and decision-making processes.

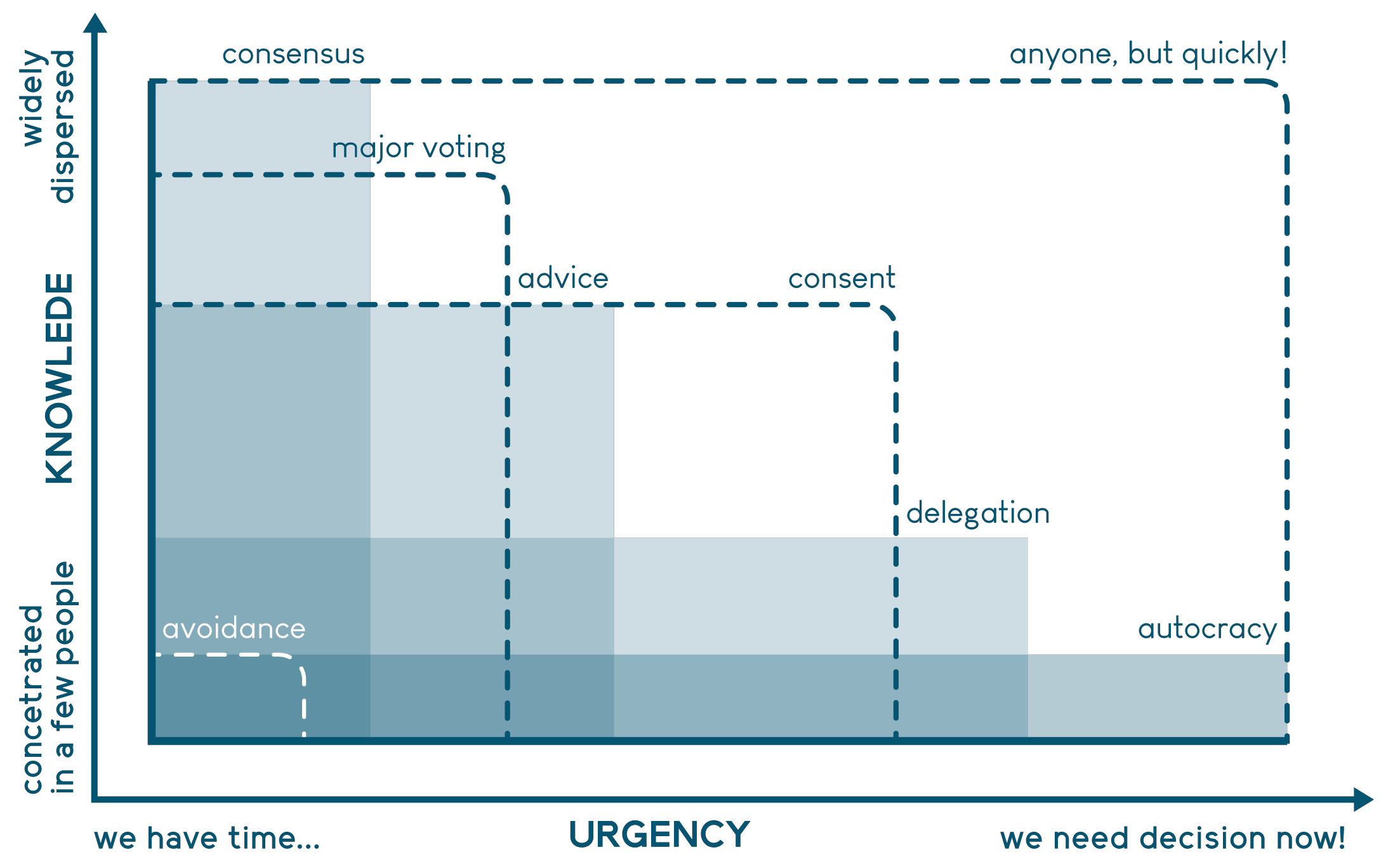

The spectrum of available decision-making mechanisms is broad. As this graph indicates, it is not necessary to choose and apply only one mechanism. Virtual communities can use multiple decision-making modalities that suit the type of decision they’re trying to make. Which mechanism you choose will be determined by how many people are needed to effectively make an informed decision as well as the time-sensitivity of the decision.

Source: Ouishare

Decision Makers

In “How to Activate Others”, you learned how to define the roles, responsibilities, and levels of participation within your virtual community. A common question you will be asked when creating decision-making processes is: Who is included and why? Not everyone in every role needs to be included in each decision. Create clear criteria to define who needs to be involved.

Divide decisions by considering the area of activity or expertise and interest of members, and be mindful of their geography. It is possible to either assemble a multi-disciplinary group that discusses all the needed areas of decision-making processes or create tailor-made groups based on decision type. However you decide to divide decision-making, it is important to ensure that your group will act in the interest of the community as a whole.

Choosing decision-making mechanisms

Once you know your community members, it’s time to begin asking important questions that will help you decide which decision-making mechanism to use. To make sure your processes grow with your virtual community over time, review and update your mechanisms regularly.

What type of decision is being made?

What are the types of decisions is your community making? Are they strategic or operative? Is there another classification that is more appropriate?

Who are the members and/or groups making the decisions?

Is everyone who should be involved (due to impact, expertise, experience) included in the decision-making?

What decision-making mechanisms will you use?

What decision-making mechanisms are aligned to your community’s values and the way it behaves?

For example, if your community is built on co-ownership and members taking the lead, choose decision-making mechanisms aligned with that model.

Tension between leadership and community

Communities typically begin under the leadership of one or more people. In order for a community to thrive, it must evolve over time to decentralise power. Leadership from one person is typically needed in the beginning to steward the community while it is growing. This leadership model comes with the power to make all initial decisions by developing a strategy, selecting a platform, and launching the community.

“When the community is more established and stable, leaders must begin decentralising power by distributings tasks among members. But holding decision-making power makes people feel needed and relevant. These feelings can make it difficult to let go of decision-making power. A great strategy is to help past leaders find a new role in the community by asking members where they think past leaders could apply their skills as they transition out of a decision making role.”

Daniel, The Borderland

Through this process, their leadership becomes servant leadership.

Hierarchies will always exist

The structure of your community must align with how decision-making power is distributed. Do not waste time trying to avoid hierarchies. They are a natural and unavoidable part of human interaction and will inevitably form. Having a flat formal structure does not prevent the creation of informal hierarchies. When members have more information and influence than others, informal hierarchies will form. Be aware of hierarchies that develop within your virtual community and change the dynamics if too much decision-making power is concentrated among certain individuals. Ongoing reflection is the key to addressing hierarchies. Don’t be afraid to have honest conversations with members who may be influencing the group out of all proportion to others in your community.

Tension between engagement and ownership

There are two key elements of decision-making (governance):

- Power

- Ownership

Tensions can occur when the people who make decisions are not legally liable (responsible) for the outcome of those decisions. This typically happens within decentralised organisations that are part of a company, or belong to an individual. Keep liability in mind when developing your community’s decision-making strategies and mechanisms. Ask yourself, how will your decision-making model give power to those who are responsible for outcomes? Will they have a veto power or a seat in strategic decision groups?

One way to avoid tension over liability is to create a distributed ownership model or cooperative. Cooperatives can face similar participation, engagement, and decentralised decision-making challenges, but they do allow members to be co-owners.

Conflict Resolution

Community managers must have a conflict resolution process prepared before a conflict or disagreement occurs. Resolution processes and procedures help to restore peace after a violation and (in the best case scenario) use the breach to learn and grow. If the governance agreements of the community are broken, you can rely on the resolution process to determine what happened, solve the problem, and steward the values of the community. Conflict resolution can also foster collective learning.

Conflict is natural in a virtual community. Do not avoid confronting or addressing conflicts in your virtual community. Avoidance endangers the health of the community and can create additional issues. If other community members see that problematic behaviour goes unaddressed, they may test the boundaries, especially if was not clearly communicated that this behaviour or action is not permitted.

To limit the number of conflicts that occur, get help from a trusted facilitator with the right skillset to steward the creation of collective agreements. When conflicts happen, address them directly. Install a mediator as soon as possible and talk to the parties face-to-face or with online meetings. Avoid written communication like emails or chats. This can lead to misinterpretation and new misunderstandings.

Conflict Resolution Steps – from Jaime Arredondo’s Open Communities’ Playbook:

- Stay calm and reassure

Rely on a trusted mediator. - Get the facts

The mediator will solicit information to find out what happened and understand the different perspectives of the conflict. - Discuss and solve

In one-on-one conversations or in a smaller group depending on the nature of the conflict. - Document and share the solution as appropriate

Share only with those involved or, if the conflict had a larger impact, share appropriate details with the virtual community. Avoid blaming language and keep your communications focused on facts and outcomes. - Reflect and maintain

Seek to understand why the conflict happened and explore options and changes that could help avoid a similar issue in the future.

Conflicts can range from misunderstandings to repeated use of inappropriate language to violation of the ground rules of the community. For example, money spent on something that was not agreed on or even seen as “misused”. Conflicts are often in the middle of this spectrum, based on misunderstanding or different views. For example: if a community has economic activity; whose customer is it? The person that first gets in touch with the client or the expert on a given topic, why does a certain project go to a certain person and not another?

Resolving conflicts in a constructive way will be much easier if a culture of non-violent communication is explicitly built into your virtual community and expressly understood by its members. Require your members to use techniques that allow them to express themselves in a constructive and respectful way. Ensure your community’s commitment to non-violent, constructive communication is clearly communicated to all members.

In its eight years of existence, Ouishare has gone from a community of bloggers interested in the Sharing Economy, to a worldwide network of passionate explorers of any topic that fosters and accelerates systemic change.

One of the keys to such a shift and further flourishing of the community is its strong working culture and its minimal and clear governance structure that allows members to easily engage in action and make decisions in an agile way.